So today we’re talking about student-created assessments. How and why did you get started with having your students design their own assessments?

First, let’s define what student-centered assessment is. It’s letting students decide how they will be assessed on whatever they’re reading.

After diving into Penny Kittle and Kelly Gallagher and the concept of student choice, David decided to let his seniors read the book of their choice in May, which went really well. While the students might not have read a class novel at that point in the year (ahhh, senior burnout, we can all relate), many of them read truly challenging books and got a lot out of it because they got to make their own choices.

The next summer David read John Spencer’s book Launch and got interested in design thinking. He decided he would try letting students design their own projects and see if he got the same increased level of investment in the projects that he had gotten with his seniors when they got to choose their own books.

He was really happy to see students bringing in their passions to the classroom to demonstrate their knowledge. The unit was a blast.

I know you encourage design thinking with this project. What are some of the hallmarks of design thinking that you build into the work?

One of the big shifts compared to the usual routine of final assessments was that they started working on the project from day one. By thinking about what it would look like early on, the students had a whole month to work on their choice projects, instead of just the last few days of the unit.

Another big focus of design thinking is that you need to design and build prototypes. It’s important to do lots of testing and checking before getting to a final product that can really matter to someone.

Here’s a quick primer on design thinking from John Spencer.

I like the way you refer to what students create as a product instead of a project. Can you explain the difference?

Part of design thinking is that you create something that will be consumed – it’s not just for class. The product will have a real audience, and might last for a while. The kids are always consuming content, so they know the deal. This ups the ante; students need to know what they’re talking about if they’re going to be putting their product out there to the world and not just to the teacher.

“Don’t make whatever it is that you’re doing look like a student project!” David tells his students. In other words, NO POWERPOINTS. NO PREZIS. NO TRI-FOLD DISPLAYS.

Once the project has begun, do you do quite a bit of workshop time and meeting with students to discuss their projects? What’s the timeline like?

They’re reading their books (which are all different!) and constructing different projects, so you need something to do together.

There are reading days and working days. There are also days when the class does skills-based prompts or writing about what they’re reading. They also do short interviews with David about the books they’ve chosen. This way he can keep a sense of how they’re processing their reading as well as how they’re doing with their projects.

Kids have the choice to work together or separately on work days. David gives them a calendar and encourages them to be planning out the different stages of the project, keeping in mind what they can best do inside of class vs. outside of class.

The PROCESS of planning, meeting, choosing what to work on and when to work on it, is one of the most important learning experiences of this unit. While the final outcome is often very special, the real world skills of process are really important ones for students to practice.

You must get such varied final products. How do you grade the work?

Start with whatever you’re going to measure – some clear standards that everyone needs to meet. David focuses this on the theme-recognition standard with some complementary grammar and speaking/listening standards. This way every student needs to keep their project close to these key focus points.

But that still leaves a problem – you just can’t assess a dance, for example, in the same way as a video. And you, as the teacher, may not know what makes a good dance.

David splits his grade of eighty points into thirty for his standards and fifty for students to break down and create their own mastery rubric hitting elements that they feel are important for the success of their project.

It helps to make sure they have a model for what they want to create – something that inspires them and gives them an example of quality work in the genre that they’re creating in. This really helps them define their mastery rubric.

Students self-assess at the end of the unit and then meet with David to talk about their projects (over the course of a couple of days while the class watches a film). They’re often too hard on themselves.

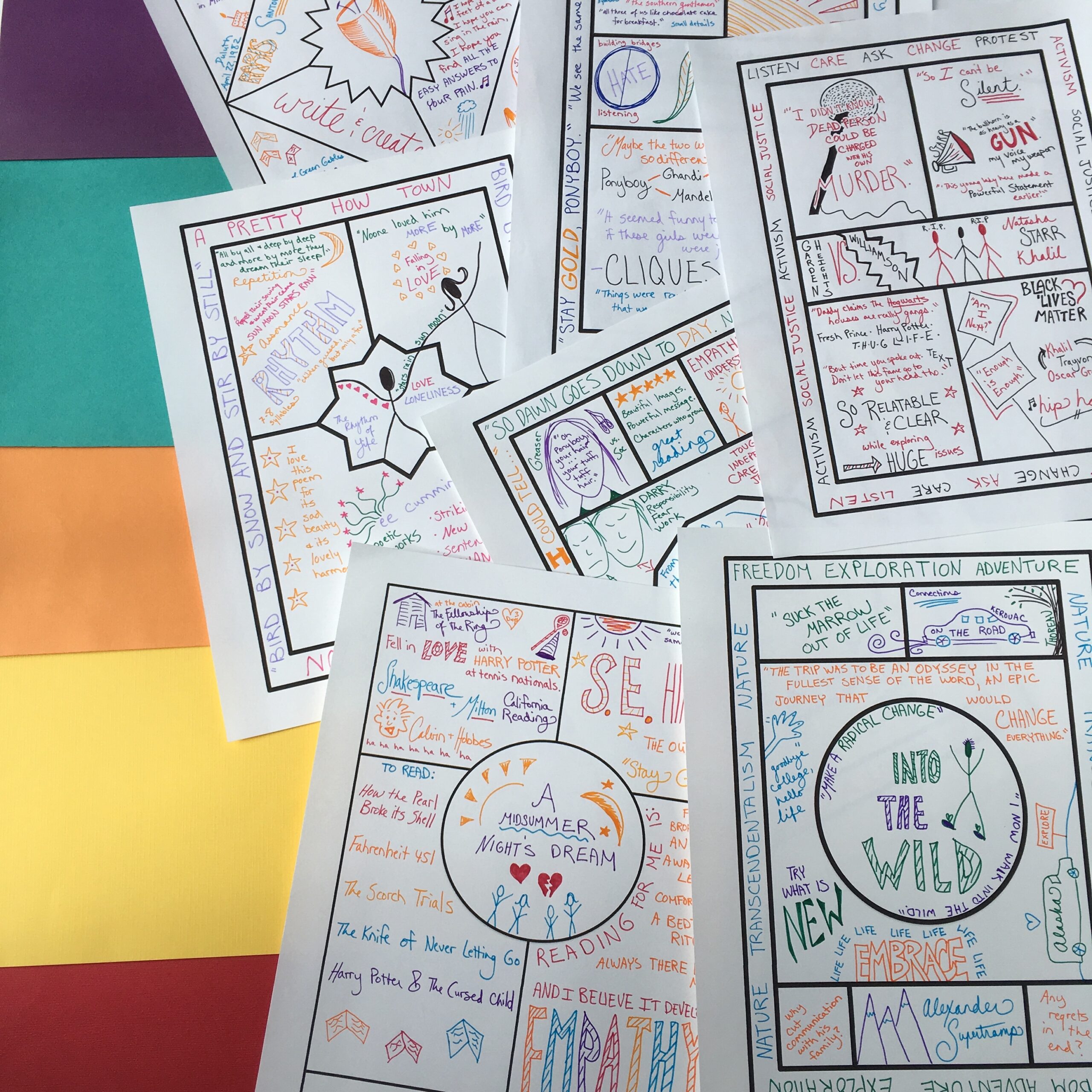

What are some of your favorite examples of things your students have done with these assessments?

“I can’t tell you how pleased I was both years that I’ve done this!”, said David, obviously delighted to be reminiscing about all the amazing projects his students have done.

One student read Huckleberry Finn, and wanted to match up music with scenes from the novel. She was a pianist, so she learned ten pieces to play for the project. Then she learned to record them and embed them onto a website.

Another student created the introductory song for a musical version of a novel, and got together a group of people to perform it.

A student created a video of himself playing a video game as Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye, narrating his choices and connecting them all to characterization.

One group threw a Gatsby party, and explained all the elements of the party and the connections to the novel on a website so someone else could throw a similar party.

Another student represented The Scarlet Letter with a makeup tutorial.

Final Thoughts

The biggest challenge of this project is just keeping up with it all, micromanaging and conferencing through it all with the students. One of the most helpful things David came up with he calls “The Think Tank.” He’d have students gather in small groups with people doing other types of projects and throw out the problems they were encountering. This was really helpful because usually other students were able to come up with solutions. This way many problems could get solved without teacher intervention, so you should definitely consider using think tanks too.

Connect with David Rickert

“I have been a Language Arts teacher for the past twenty years and have taught several different classes from Creative Writing to inclusion classes to honors classes. I currently teach English 9, AP Literature and Composition, and a dual enrollment class through Kenyon College. My entire teaching career has been with Hilliard City Schools, a suburb of Columbus, Ohio.” -David

David writes on so many wonderful creative topics, including ways to help students connect to ELA through visual mediums. Check out his website here.

Do you find your inspiration in VISUALS? I love ‘em too. Let’s hang out on Instagram! Click here to get a steady stream of colorful ideas all week long.