Welcome to episode 150! Today we have a very special guest in Penny Kittle. We’re talking about choice reading, teaching writer’s craft through modern mentor texts and writer’s notebooks, why teaching narrative just might be more important than focusing on argument so much, and more!

Let me give you some background on Penny’s amazing career in the form of a quick bio from her website, and then we’ll jump into the conversation.

“Penny Kittle teaches freshman composition at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire. She was a teacher and literacy coach in public schools for 34 years, 21 of those spent at Kennett High School in North Conway. She is the co-author of180 Days with Kelly Gallagher, and is the author of Book Love, and Write Beside Them, which won the James Britton award. She also co-authored two books with her mentor, Don Graves, and co-edited (with Tom Newkirk) a collection of Graves’ work, Children Want to Write.

She is the president of the Book Love Foundation and was given the Exemplary Leader Award from NCTE’s Conference on English Leadership. In the summer Penny teaches graduate students at the University of New Hampshire Literacy Institutes. Throughout the year, she travels across the U.S. and Canada (and once in awhile quite a bit farther) speaking to teachers about empowering students through independence in literacy. She believes in curiosity, engagement, and deep thinking in schools for both students and their teachers.

Penny stands on the shoulders of her mentors, the Dons (Murray & Graves), and the Toms (Newkirk & Romano), in her belief that intentional teaching in a reading and writing workshop brings the greatest student investment and learning in a classroom.”

The more I have studied Penny’s work, the more I feel connected to it. I truly believe you will be inspired by her words, and I hope you’ll order one (or all) of her books after listening to this episode!

You can listen in on the podcast player below, or on any of these lovely platforms. Or, read on for highlights and links!

Let’s Start with the Revolution

One of the things I find helpful about Penny’s stories is that she has repeatedly been through the process of gently challenging things that don’t work at her different schools. So that’s where we started our conversation, with the question of how to reject the things that aren’t working in education and choose creativity, choice, and a focus on what students really need instead.

Penny has worked in six different states over thirty-four years in public schools, which means she has experienced school from many different lenses. As she says, it can sometimes feel like whatever your school does is just the way school is, but once you begin to move around between grade levels and systems and states, you see that each school is making decisions about how to treat children and how to approach the teaching of reading and writing.

And that means those decisions aren’t unalterable.

Penny found that when it came time to challenge a practice she felt wasn’t best serving students, it helped to understand her own beliefs. Because she focused on responsive teaching, centering her practice on what the students in the room needed, she was driven to look for solutions to the problems she discovered and to try to design programs that would bring students joy in reading and writing.

When she moved from 8th grade to 9th grade, she went from watching her younger students read 30 or 40 books a year to being handed four books that every student in her new course must read.

Why those books? She wondered. And why only four?

When she was handed a complicated grammar textbook for her students at one school, she chose another path to teach her students writer’s craft. When her principal asked why she wasn’t using the grammar text, she flipped to a random page and asked the principal if she knew the definition of the word on the page, or how to use it in a grammar construction. The principal had already seen the choices she was making around the teaching of writing, and that she cared deeply. When she admitted that she didn’t know the word or how to use it in writing, she was giving Penny the green light to keep doing what she was doing.

Over and over, throughout Penny’s career, she bumped into folks who were doing it other ways, and sometimes viewed her with some hostility. But she believed it was legitimate for teachers to ask questions of practice of each other.

She tried to approach these conversations with empathy, humility, research, and confidence. Sometimes she invited others into her classroom, or suggested they read and discuss an article together to gain a greater understanding of the concept.

PUT IT INTO PRACTICE:

When you see something you don’t agree with, try one of Penny’s approaches. Get clear on your research and your purpose, and then gently question what is happening and share some alternative possibilities. Invite others to read an article with you, visit your classroom, or take a look inside the textbook they’ve given you to see if they really believe in it more than what you’re suggesting.

From Apathy to Engagement in Reading

The sad truth is that students are reading less than ever, and I think we all join Penny in being dismayed over this. Change seems to be coming one classroom at a time, and not in a sweeping overhaul of our education system, so we bring choice into our curriculum as much as we can.

Students need that chance to truly engage in an experience with a book. They need to have it grab them and name things in their heart and mind that they didn’t even know they were struggling with. They need to have the experience of not being able to put it down and remember what that feels like.

It’s not enough just to tell students about books. Penny’s program includes book talks every day with a “Next to read” list in the back of their notebooks, fifteen minutes of time to read (and for her to confer with kids about their reading) and a pile of books on every table for “speed dating” when kids are looking for a new book.

Penny book talks everything she can find that students might connect to – books on hunting and fishing, basketball books, memoirs, collections of poetry, and much more.

As she confers with kids, she’s always watching for that kid who looks like they can’t wait for the reading time to end, and making sure she gets to them. Kids who come to her never having loved a book present her with a challenge she thinks about outside of class – would an audiobook help? Which book might help them remember what it’s like to love reading? Or find out for the first time?

When a student is struggling to stay with the book or keeps zoning out, she’ll ask “When did you last know what was going on?” and reinforce that this happens to every reader, then share a strategy she uses for catching back up with what is going on and continuing.

As Penny puts it, kids need to practice making meaning from the book. Independently. She quotes Kylene Beers, who writes, “A book is like a barbell on the floor of a gym.” It doesn’t matter what it means or what it can do if you don’t pick it up and start doing something with it. We want to get all the kids lifting, and that means you help them start to make meaning from a text without anyone else.

Penny recalls sharing her choice reading concepts with another teacher who was feeling skeptical. Then a boy came into her colleague’s class who hadn’t really ever read a book, and he had what Penny calls “that look” in his eyes. “We’ve gotta talk about this book!” he said, and it changed the way her colleague saw the teaching of reading.

PUT IT INTO PRACTICE:

Take time for books talks and choice reading in class. Confer with kids about what they enjoy and how they’re doing. Add books to common spaces for “speed dating.” Get kids started with a “Next to Read” list.

Curating Modern Work to help Inspire Student Writers

One of the hallmarks of Penny’s method for teaching writing is the way she collects and curates short modern works that are meaningful to students. Works that inspire their writing. She shared four of the ways she goes about this.

First of all, listen to the students. They’re so good at finding good things! When her students asked her to stop playing Taylor Swift and gave her a new musician to play, Penny soon put the lyrics up as writing inspiration. As Penny says, you want to be in the world your students are in.

Second, Penny reads so much and she collects and shares the best of what she finds. For example, after finding an intriguing piece in The New York Times called “The No Good Very Bad Truth of What’s on the Internet,” she had her students check their screen time usage on their phone, read the piece, and then write alongside it with their thoughts and reactions.

Third, she goes to conferences and learns from others. She tries out the incredible resources others recommend.

Finally, she signs up for things like receiving the poem of the day from poetry websites. Right now she gets three different poems every day from three different sites. Sometimes she just deletes them without having time to read them, but other times she finds something wonderful.

PUT IT INTO PRACTICE:

Add a bookmarks folder for modern mentors to your computer or start a curated collection on your favorite curation app. Add suggestions from your students, your own favorite work as you find it, recommendations you pick up at conferences or on social media, and meaningful pieces that come your way through emails from your favorite organizations.

GRAB THE RESOURCE: Check out Penny’s amazing Padlet of Inspiration!

From Disaffected to Engaged Writer with Writer’s Notebooks

Students now taking Penny’s college courses are often in the same boat – they are masters of a scripted five paragraph essay, but unsure of how to think and create as independent writers. And just as with her high school students, she helps them gradually back to the craft of writing through their writer’s notebooks.

Her students often think they’re not good at writing. They watch Ted Talks and TikToks and they lack confidence in their ability to speak as they see others speaking – which is rooted in their writing.

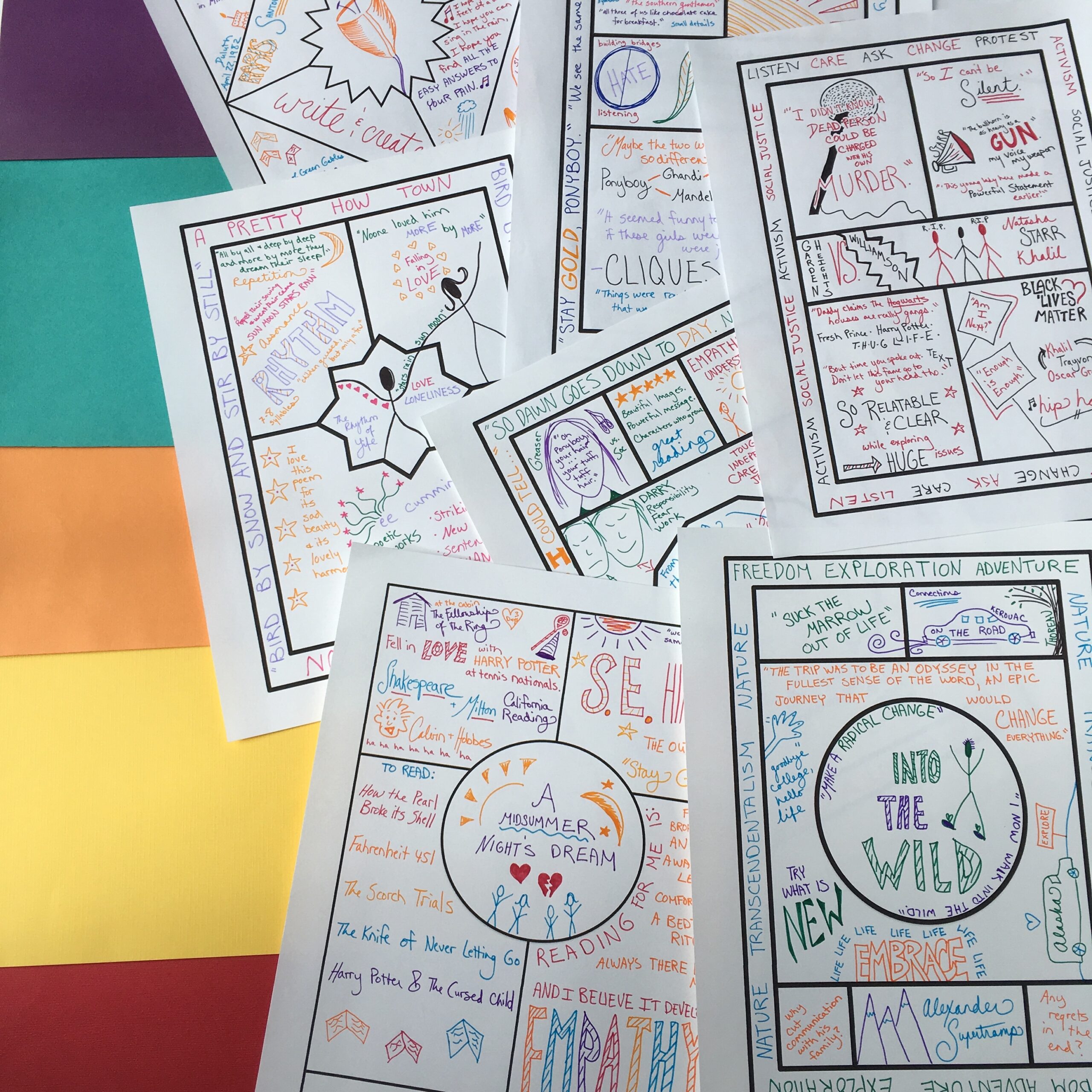

Enter, the writer’s notebook, Penny’s vital tool. Her students do daily writing practice in class in their notebooks with just two rules – you can’t do it wrong, and if you can’t think what to write, just sketch.

Sometimes they write alongside a text, examining and trying out a craft move. Penny asks them to notice a move in a piece and figure out what it does. They start with labels, like “that’s a flashback.” But she pushes them to figure out what its purpose is – what’s the point of the flashback? What is it accomplishing in the piece?

Just like students keep a running list of books they’d like to read, they keep a running list of craft moves they’d like to try.

Penny writes too, in her own writer’s notebook, generally under the document camera so students can see a model if they’d like to. “I find writing endlessly fascinating,” she says. “And so I try to bring that to class.”

As the writing time comes to a close, Penny invites students to do a whipshare. They can read aloud a line, a phrase, a passage, or pass. She calls every student by name, and in quick succession they share. Students get to see sooooo many ways to respond to a single prompt, and also find connections with others. This is a crucial piece of community building for the class, especially now after all the isolation of quarantine. It’s also a quick confidence builder for many kids.

Penny will sometimes spotlight a student’s work (with permission). She might pull a notebook under the document camera and say, “Let’s just take a minute to see what Emma did here…” and then gives Emma time to explain her writing choices.

PUT IT INTO PRACTICE:

Give students time to explore modern mentor texts and discuss the writer’s craft moves inside. Take time to practice writing often through engaging, relevant prompts, with the invitation to try out the writer’s craft moves they are discovering through the mentor texts. At the end of writing time, invite every student, by name, to share a line, a phrase, or a passage if they wish, or to say pass.

Centering Narrative in Writing Instruction

Penny gives a lot of time to teaching narrative in her writing instruction. She teaches kids to create scenes, then to build several scenes, then to knit them together. Her friend Tom Newkirk wrote a book called Minds Made for Stories that she references to explain why.

Newkirk suggests we really shouldn’t use narrative writing as a category like “informational writing” or “argument writing.” Instead, he says, narrative is the way we frame our thinking and our lives. It holds a central place in the way we, as humans, have always interpreted the happenings in our world.

“We use story to say ‘I was here,'” says Penny. That is quite different than using writing for other purposes. Story marks who we are and where we are. Narrative is a form that exists within all other forms, so “of course! Of course we want kids to write a lot of narrative!”

Top Picks for Choice Reading right Now

I had to ask Penny for her top choice reading picks at this moment. Here are her recommendations for middle school…

And for high school…

Connect with Penny Kittle

Learn more about Penny Kittle’s Book Love Foundation.

In need of funding for your developing class library? You could apply for a grant!

Want to dive deeper into your practice with Penny this summer? Join the summer book club!

If you’d like to find out if Penny is speaking near you this year, check out her speaking schedule.

Before you Go

In search of a creative kickstart you can use right away? Visit the free resources section and get started with one-pagers, hexagonal thinking, literary food trucks, and more!

2 Comments

Excellent podcast with Penny Kittle. I have followed her for a few years and can highly recommend the Summer program. Thank you for asking about reaching tough to enjoy reading and writing students. I loved her advice.

I’m so glad you found the episode helpful! And thank you for sharing your experience of the summer program too!