So you love what you’re seeing about hexagonal thinking around the web, but you just can’t quite wrap your head around getting started with this creative discussion strategy. I hear you! I’ve been getting lots of great questions about how to make a set of hexagons for a first go-round, and I’m going to answer them all in this episode. Get ready to find out all the details about what to put on, who should put it on, and who should be doing the cutting out!

If you’re unfamiliar with hexagonal thinking, check out this post for an introduction. And grab your free editable hexagonal thinking toolkit right here.

OK, now let’s dive into hexagonal thinking decks. You can listen in below, or on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or whatever podcast player you love.

What do I put on my hexagons?

So you’re looking at a set of blank hexagons and wondering, what terms and ideas are going to create productive discussion and original connections?

Relax, you’ve got all the answers already! The exact same kinds of things you would normally bring up in discussion can go on your hexagons, plus you can play around with adding more connections related to current events, historical events, and interdisciplinary topics.

For example, when thinking about a novel, you might add some of these core components to your hexagons:

- character names

- themes

- symbols

- literary devices that are important to the text

- key elements of the author’s style

- quotations

- setting elements

And then you might think beyond the core components, considering connections like these:

- related ideas from the art of the period

- related events, movements, novels, films, or figures from the modern day

- related events or movements from history

- related characters, themes, or concepts from elsewhere in your curriculum

Your goal with your hexagons is to stir up discussion about how all these puzzle pieces can fit together.

Let’s look at Jason Reynold’s novel, Lu, the fourth installment of his Track series, as an example.

I’d start by adding key characters – like Lu, Otis, Goose, Patina, Ghost, Sunny, and Whit. Then I’d add the themes of integrity and bullying. I’d pull Lu’s gold chains and Otis’s gold medal as key symbols. I’d put in Glass Manor and Crenshaw Heights as setting elements. I’d choose some quotations that I felt students would resonate with as important to the themes and arc of the novel.

Then I’d add some concepts like drug use and rehabilitation, possibly bringing in the opioid crisis as a related current event. I’d potentially make inter-curricular connections to other books with similar themes, depending on what we had read before approaching this novel. If my students had read more of Jason Reynold’s books, I would certainly add big ideas from those books as well.

Who should put the terms on – me or my students?

So now you might be wondering, do I hand some of this concept brainstorming off to my students? The answer is sure, if you want to.

Here’s what I suggest.

The first time you try hexagonal thinking, your students are just learning the strategy. They don’t really know what the cards are for, so it’s going to be a little more confusing for them to create a good deck.

I see a lot teachers introducing the strategy with a deck full of fun cards their students will connect to (picture t.v. shows, candy, or popular slang terms), but even if you dive straight into your main content, I think it makes sense to give kids all the terms on their first deck. That way all they need to figure out is how to start making connections, and it’s simpler for everyone.

The second time you launch hexagonal thinking (and I do hope you use it as a regular strategy, not a one-off, because students are only going to get better at it), you might consider letting students create some or all of the cards. You could have a core set of terms defined for each group and let them add an additional set that they come up with themselves, or you could put the categories (characters, themes, etc.) up on the board and ask them to come up with their own complete deck, with a certain amount of terms in each category. Or maybe you do the core connections (from the first list of components), and invite them to add the cross-curricular connections and the connections to current events (the second list of components).

Who should be cutting these out? Do I need some kind of special hole punch? A laminator? A personal assistant who specializes in intricate cutting?

This is a key question when it comes to hexagonal thinking! First things first, there are a lot of ways to print these hexagons (or you can use digital ones, like in this free kit). You can print small or large hexagons, use regular paper or cardstock, or even laminate your hexagons. I recommend printing them relatively small and on cardstock most of the time, though large decks, laminated decks, and even large laminated decks can be fun in certain situations!

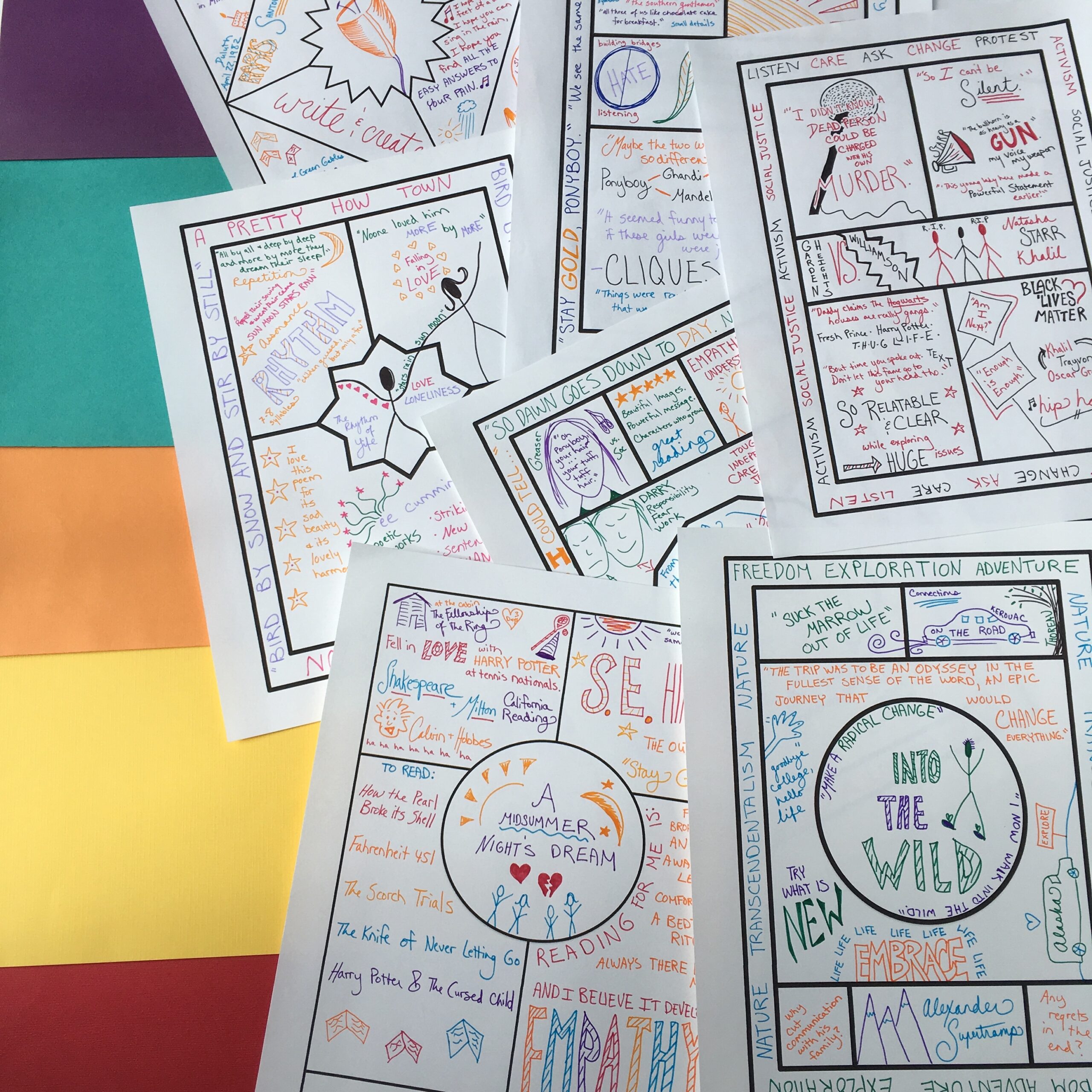

When it comes to cutting, I recommend getting your students in on the job. Unless you are going to go the lamination route, in which case maybe you pull up an episode of Schitt’s Creek and cut out five or six rainbow decks (like these free ones) you can use over and over. Then you can put term lists on the board and have students add them to the hexagons. But otherwise, print your decks (with terms or without) for each group of students that will be using them, then pass them out along with some scissors to get the activity rolling. With a group of kids cutting out their own deck, it will only take a minute or two.

You don’t need any special equipment or to spend three hours cutting the night before! Just let the kids help.

I hope you’re feeling more confident about how to create your hexagonal thinking decks now, because I think you’re going to love using hexagonal thinking in your classroom!